Summary

Notes

My current favorite prosthesis is the class of software that exploits the spacing effect [Spacing effect], a centuries-old observation in cognitive psychology, to achieve results in studying or memorization much better than conventional student techniques; it is, alas, obscure.

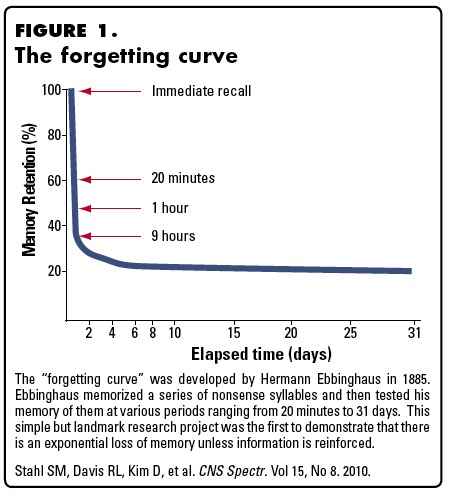

The spacing effect essentially says that if you have a question (“What is the fifth letter in this random sequence you learned?”), and you can only study it, say, 5 times, then your memory of the answer (’e’) will be strongest if you spread your 5 tries out over a long period of time - days, weeks, and months. One of the worst things you can do is blow your 5 tries within a day or two. You can think of the ‘forgetting curve’ [Forgetting curve] as being like a chart of a radioactive half-life: each review bumps your memory up in strength 50% of the chart, say, but review doesn’t do much in the early days because the memory simply hasn’t decayed much! […]

A graphical representation of the forgetting curve:

Even better, it’s known that active recall is a far superior method of learning than simply passively being exposed to information.6 Spacing also scales to huge quantities of information; […]

If you’re go good, why aren’t you rich?

Of course, [cramming] is precisely what students do. They cram the night before the test, and a month later can’t remember anything. So why do people do it? (I’m not innocent myself.) Why is spaced repetition so dreadfully unpopular, even among the people who try it once?

Because it does work. Sort of. Cramming is a trade-off: you trade a strong memory now for weak memory later. (Very weak12.) And tests are usually of all the new material, with occasional old questions, so this strategy pays off! […]

Across experiments, spacing was more effective than massing for 90% of the participants, yet after the first study session, 72% of the participants believed that massing had been more effective than spacing….When they do consider spacing, they often exhibit the illusion that massed study is more effective than spaced study, even when the reverse is true (Dunlosky & Nelson, 1994 (a); Kornell & Bjork, 2008a; Simon & Bjork2001 (a); Zechmeister & Shaughnessy, 1980 (a)).

As one would expect if the testing and spacing effects are real things, students who naturally test themselves and study well in advance of exams tend to have higher GPAs. If we interpret questions as tests, we are not surprised to see that 1-on-1 tutoring works dramatically better (a) [Bloom’s 2 sigma problem] than regular teaching and that tutored students answer orders of magnitude more questions.

This short-term perspective is not a good thing in the long term, of course. Knowledge builds on knowledge; one is not learning independent bits of trivia [Andy Matuschak | Knowledge Work Should Accrete]. Richard Hamming recalls in “You and Your Research”:

You observe that most great scientists have tremendous drive. I worked for ten years with John Tukey at Bell Labs. He had tremendous drive. One day about three or four years after I joined, I discovered that John Tukey was slightly younger than I was. John was a genius and I clearly was not. Well I went storming into Bode’s office and said, “How can anybody my age know as much as John Tukey does?” He leaned back in his chair, put his hands behind his head, grinned slightly, and said, “You would be surprised Hamming, how much you would know if you worked as hard as he did that many years.” I simply slunk out of the office!

What Bode was saying was this: “Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest.” Given two people of approximately the same ability and one person who works 10% more than the other, the latter will more than twice outproduce the former. The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity - it is very much like compound interest. I don’t want to give you a rate, but it is a very high rate. Given two people with exactly the same ability, the one person who manages day in and day out to get in one more hour of thinking will be tremendously more productive over a lifetime. I took Bode’s remark to heart; I spent a good deal more of my time for some years trying to work a bit harder and I found, in fact, I could get more work done.

This long term focus may explain why explicit spaced repetition is an uncommon studying technique: the pay-off is distant & counterintuitive, the cost of self-control near & vivid. (See hyperbolic discounting (a).)

Literature review

Review summary

To bring it all together with the gist:

testing is effective and comes with minimal negative factors (a)

expanding spacing is roughly as good as or better than (wide) fixed intervals, but expanding is more convenient and the default

testing (and hence spacing) is best on intellectual, highly factual, verbal domains, but may still work in many low-level domains

the research favors questions which force the user to use their memory as much as possible; in descending order of preference:

- free recall

- short answers

- multiple-choice

- Cloze deletion

- recognition

the research literature is comprehensive and most questions have been answered - somewhere.

the most common mistakes with spaced repetition are

Using it

How much to add

[…] That’s our key rule of thumb that lets us decide what to learn and what to forget: if, over your lifetime, you will spend more than 5 minutes looking something up or will lose more than 5 minutes as a result of not knowing something, then it’s worthwhile to memorize it with spaced repetition. 5 minutes is the line that divides trivia from useful data. (There might seem to be thousands of flashcards that meet the 5 minute rule. That’s fine. Spaced repetition can accommodate dozens of thousands of cards. […])

The workload

On average, when I’m studying a new topic, I’ll add 3-20 questions a day. Combined with my particular memory, I usually review about 90 or 100 items a day (out of the total >18,300). This takes under 20 minutes, which is not too bad.

When to review

When should one review? In the morning? In the evening? Any old time? The studies demonstrating the spacing effect do not control or vary the time of day, so in one sense, the answer is: it doesn’t matter - if it did matter, there would be considerable variance in how effective the effect is based on when a particular study had its subjects do their reviews.

So one reviews at whatever time is convenient. Convenience makes one more likely to stick with it, and sticking with it overpowers any temporary improvement.