Summary

- Legibility as singular: Overriding all other ways of being and forcing us to live within the mind of its creator.

- Legibility as faceted: Complements our own experience; allows us to apply it where we see fit

Thoughts

This dichotomy reminds me of Unix philosophy; Composability versus monolithic design.

Notes

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott defines “legibility” [Legibility] as something a state imposes on its people and resources. It is a coercive abstraction, not only treating different people, places, and ways of life as if they were the same, but creating an environment which encourages people to forget those differences ever existed.

One of Scott’s first examples is land ownership in pre-modern rural villages, each of which had its own peculiar practices built over generations, describing the obligations between neighbors, the obligations between relatives, and the use of common pastures and forests. These practices were perfectly legible within a given village, but a cacophonous mess to state officials trying to understand all of them at once.

And so the states sent in surveyors, who drew sharp boundaries on their maps. A year later came the tax collectors, maps in hand. If a family paid taxes on what was once common property, they had little motivation to let their neighbors continue to use it. Instead, the villagers reshaped their lives to fit the maps.

In The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch defines “legibility” as something that a complex environment offers to its inhabitants, allowing them to easily navigate it. It is a clarifying abstraction, making the world more than an endless deluge of minute details.

Lynch interviewed long-time residents of various cities, and asked them to describe how they’d navigate from one part of the city to another. He created reference maps of shared elements from these journeys, representing how each city was understood by its people.

In software, for instance, anywhere one implementation cannot be easily exchanged for another, users are forced to bend themselves to the needs of their software. [Not in Emacs!]

This is worrisome, not least because of the tech industry’s continuous attempts to resurrect logical positivism (a). Someone who claims their design was conceived from first principles has almost always injected their own biases and incuriosity into those principles. As coercive abstractions, these designs will preserve whatever is familiar to a small, homogeneous group, and allow everything else to wither away.

Scott offers prescriptions for avoiding the problems he describes, but they’re mostly process-oriented (“take small steps”, “favor reversibility”) and entirely focused on harm reduction. For Scott, abstraction is always something done to people, never for people.

The legibility described in Seeing Like a State, and imposed by Palmer Eldritch, is singular; It overrides our own experience, forcing us to live within the mind of its creator. The legibility described in Image of the City, and offered by Marco Polo, is faceted; it complements our own experience, allowing us to apply it where we see fit.

Creating singular legibility is simple: find something that’s easy for you to understand, and force people to use it. What’s hard is using it responsibly; to predict its full effect, you’d need to first have an exhaustive understanding of the environments in which it will be used.

Faceted legibility is more forgiving, allowing us to understand the world incrementally and collaboratively. It’s not, however, something we can simply create on our own. Instead, we can only lay the groundwork and hope it flourishes.

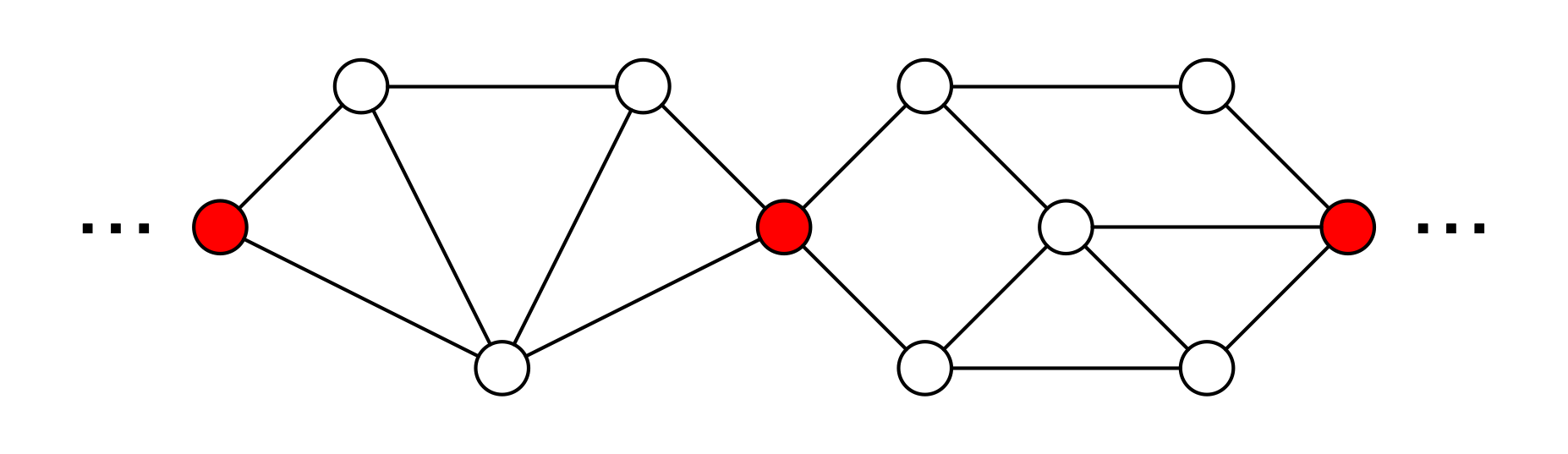

But if you, like me, are interested in software, there are no readymade references.5 I believe, however, that the answer lies in articulation points:

As we compose our abstractions, we must ensure we create, at regular intervals, interfaces which fully separate our upstream and downstream components. These interfaces not only delineate subgraphs which can be understood in isolation [Black boxes], they represent decision points in our design process. From any given articulation point, we can branch off in a dozen different directions, perhaps even all at once. These are separate interpretations of what the interface represents, each of which can be considered or ignored in isolation.

This is more easily said than done. Countless decisions go into every bit of software, but not all of them deserve to be enshrined as an interface. Once used, interfaces ossify. They allow the code on either side to drift apart, to lose consistency in idiom and purpose. If we don’t expect an interface to require multiple interpretations, it shouldn’t exist. To make the right decision, we must predict the future.