Recognition-primed decision (RPD) is a model of how people make quick, effective decisions when faced with complex situations.

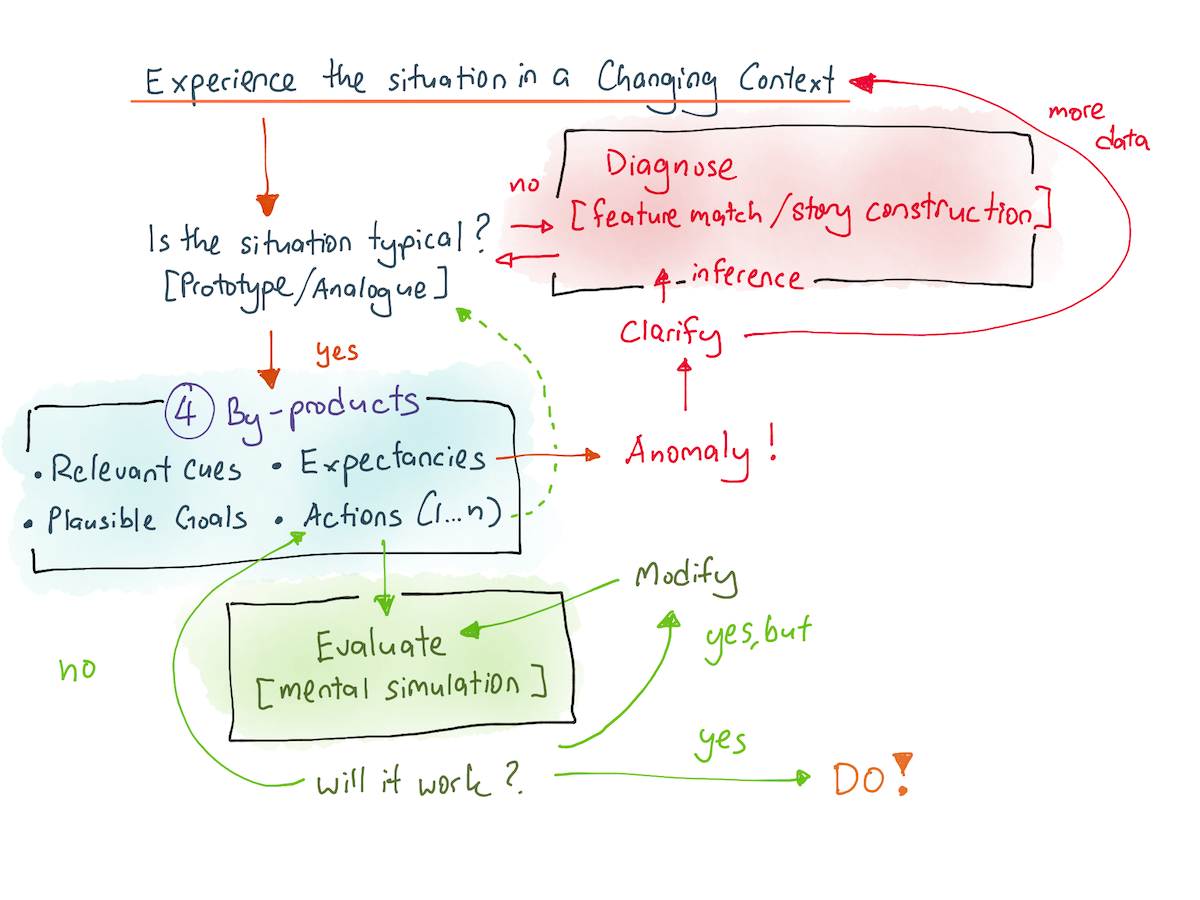

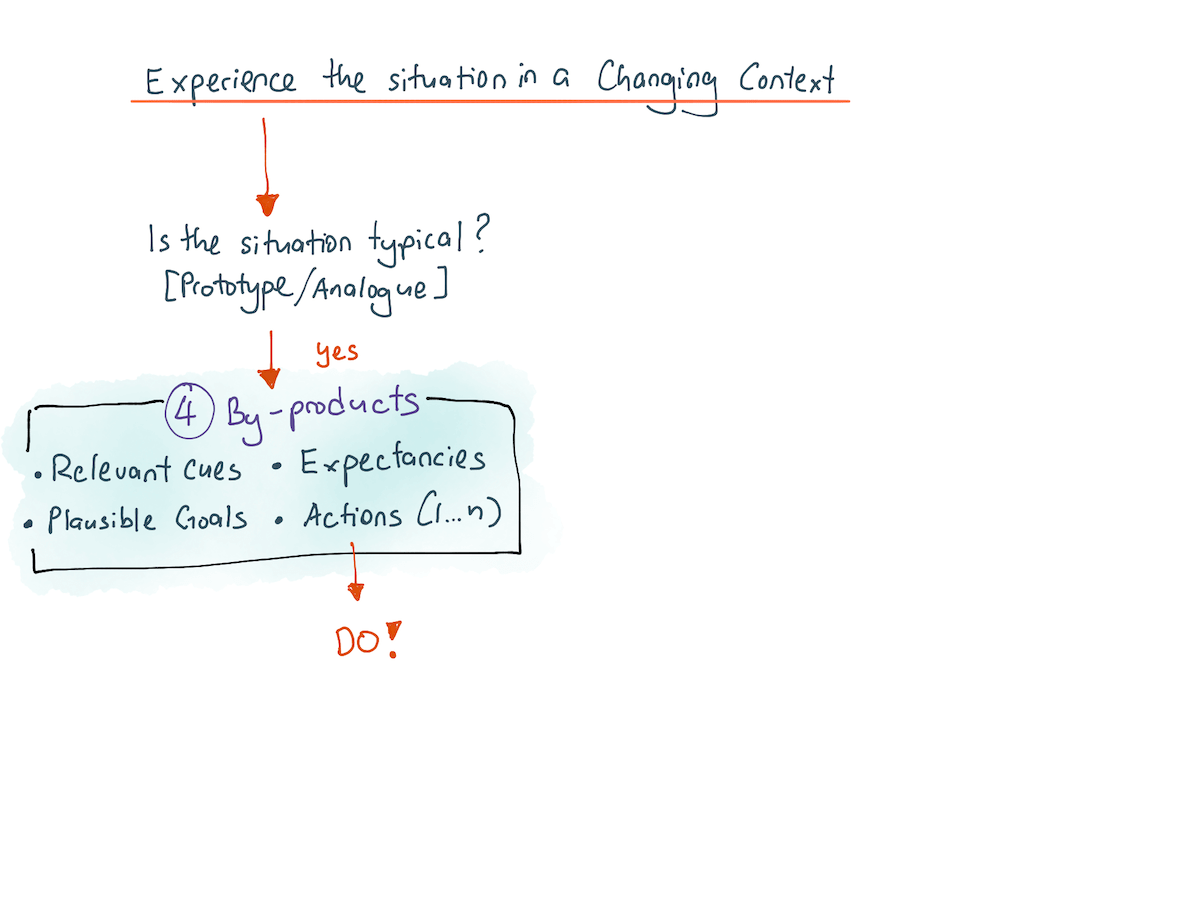

In general, it’s a pattern-matching exercise (see Cedric Chin | Expertise Is ‘Just’ Pattern Matching): recognize the situation at hand and choose the best already-known course of action. This presupposes that you (1) can recognize the situation and (2) know the right course of action. If either supposition is false, then refer to the flow chart:

How to improve at Recognition-primed decision making?

Systematically Expand the Set of Prototypes You Have

The first method of application follows easily from the model: because so much of expertise is pattern matching, many of the training programs that are designed by NDM [Naturalistic decision making] practitioners are oriented around expanding the set of prototypes in their learners’s heads. […] seek out situations where you have less experience, in order to expand the set of prototypes in your head. Another way might be to select and use exercises that help build out the prototypes you have; […]

Identify When A Practitioner Has a Prototype That You Do Not

Another, less obvious way to use RPD is to identify when a practitioner is using her intuition. When you notice a practitioner making a rapid assessment of a problem, when they say “it just felt right”, or when they give you an explanation that is full of caveats and gotchas, you now know that they are using an implicit-memory recognition operation that stems from their experiences. If you face a similar situation and you find yourself doing option comparison, this should tell you that your colleague has a prototype that you do not, and that this might be something you want to acquire.

In other words, you can use this to build a skill tree for yourself.

RPD is useful because you should also know to ask about the cues, expectancies, priorities, and courses of actions that present themselves in the practitioner’s mind. Don’t get me wrong: this will not be a good extraction of their tacit knowledge, because expert intuition is difficult to explicate, and CTA is itself difficult. But it’s surprisingly useful to just ask questions along these lines […]

Get Better At Mental Simulations

A second lever that falls out of the RPD model is the idea of giving learners sufficient experiences in order to simulate effectively.

Recall that mental simulation is a key part of RPD: it drives the identification of expectancies, and it allows practitioners to simulate possible courses of action before picking one to execute. More experiences mean more accurate mental simulations.

[…]

Sometimes, it’s just plain difficult to create appropriate training programs for yourself. One way around this is to reflect on your past experiences, and then go to more skilful practitioners to get feedback on the actions that you chose in past events.

When doing so, it’s important to copy the method that’s used in CTA: you should describe the event linearly, as you experienced it, never revealing more information than you had at the time. For instance, if you want to make better decisions around managing people, you might choose to describe an experience where a subordinate reacted negatively to you, and walk through that event as it unfolded. You should not tell the expert what you discovered later, after the events had already transpired. In simple terms: you should put the expert in your shoes.

When doing this, compare:

- What cues it was that you noticed vs what cues they picked up on. (Sometimes this could be expressed in the follow-up questions they ask during your story-telling.)

- What you expected to happen next vs what they expected to happen next.

- What actions you thought to do vs what actions they thought to do,

- And finally: what priorities you had in that situation, vs what priorities they might have instead.

I’ve adapted this idea from Klein’s cognitive critique […]

(Chin 2020), formatting mine

Notes

Recognition-primed decision (RPD) is a model of how people make quick, effective decisions when faced with complex situations. In this model, the decision maker is assumed to generate a possible course of action, compare it to the constraints imposed by the situation, and select the first course of action that is not rejected [Satisficing]. RPD has been described in diverse groups including trauma nurses, fireground commanders, chess players, and stock market traders. It functions well in conditions of time pressure, and in which information is partial and goals poorly defined. The limitations of RPD include the need for extensive experience among decision-makers (in order to correctly recognize the salient features of a problem and model solutions) and the problem of the failure of recognition and modeling in unusual or misidentified circumstances.

There are three variations in RPD strategy.

- If …, then …: Decision makers recognize the situation as typical: a scenario where both the situational detail and the detail of relevant courses of action are known.

- If (???), then …: The decision maker diagnoses an unknown situation to choose from a known selection of courses of action.

- If …, then (???): The decision maker is knowledgeable of the situation but unaware of the proper course of action. The decision maker therefore implements a mental trial and error simulation to develop the most effective course of action.

(“Recognition-Primed Decision” 2023), paraphrased, formatting mine

The recognition-primed decision making model describes what humans do when they are problem solving in the real world. It tells us that when an expert encounters a problem in the wild, their brain observes the situation in a changing environment and immediately pattern matches it against a collection of prototypes. If they recognise what they see as an example of a prototype — even if the situation they see is non-routine! — their brain immediately generates four things:

- A set of ’expectancies’— When diagnosing a situation, experts will construct mental simulations of how the events have been evolving and will continue to evolve. In other words, they will have some expectations for what happens next. The more experienced they are, the more clear-cut these expectancies become. For example, an experienced firefighter might take in a scene and know instantly where the fire might travel, or how a bad situation might develop. A programmer reading a codebase might find several weird kludges, and immediately suspect a submodule to be a persistent source of bugs.

- A set of plausible goals — The expert would know what to prioritise in the moment, and what to defer to a latter time. When under fire, for instance, a Marine Corps squad leader would have to prioritise between keeping his people alive, getting to better cover, and achieving mission objectives. His recognised prototype tells him where his priorities lie in a given situation, freeing cognitive resources to conduct other forms of thinking. Similarly, a programmer may receive a set of business requirements, and immediately generate a prioritised list of goals in their head according to the recognised prototype.

- A set of relevant cues — Experts know what to pay attention to; novices do not. Recognised prototypes come with a set of cues — for instance, when you’ve just started driving, you may find yourself overwhelmed with the dials and knobs and mirrors you have to keep track of. After a few months, however, you do these things automatically, and shift your attention to specific affordances in your car depending on the situation. (For instance, when turning a corner, you know to check your side mirrors and you know what to watch out for.)

- An action script — Last, but not least, if the situation is typical, the expert would have a course of action immediately generated in their heads. If the situation is not typical, the expert’s brain would still generate a set of actions, but the expert would slow down to walk through each action step in their head.

The recognition of goals, cues, expectancies and actions is part of what it means to recognise a situation. What is important to understand is that all of this recognition happens within implicit memory. This is why experts are not able to verbalise what they are doing.

Implicit memory operations are subconscious. Our ability to recognise faces, for instance, is an implicit memory operation, and we cannot say how it happens. When your friend Mary walks into the room, you immediately recognise her face. But notice that remembering her name is a different process entirely: this is because facial recognition is recognition; name retrieval is recall, and the two operations use different subsystems in your brain. (Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984 (a))

When an expert says “it just felt right”, what they mean to say is that they recognised the problem as an example of a prototype in their heads, which generated the four by-products; this implicit memory operation happens so quickly that they cannot verbalise how they came up with it. They can only say “it just felt right!”, the same way you might say of an acquaintance: “I know her, I just can’t remember her name!”

[…]

In most cases, however, the default human response is to satisfice: that is, to generate and then cycle through actions one at a time until the first suitable one is found.

RPD is useful because it gives us a model with which to understand human expertise. When you apprentice under someone, what’s actually happening is that you are building up prototypes in your implicit memory — that is, you are identifying cues, learning plausible goals, internalising action scripts, and storing expectancies. At the same time, you are also collecting the experiences necessary to simulate action scripts in your head.

Klein mentions that RPD is similar to other models of expertise, such as Lee Beach and Terry Mitchell (a) on image theory, the skills-rules-knowledge scheme (a) by Jens Rasmussen, and other models of expertise by P. A. Anderson (a), Wohl (a), and Dreyfus and Dreyfus (a). According to Klein (Sources of Power, Chapter 7), RPD’s contribution is merely that:

- It appears to describe the decision strategy used most frequently by people with experience.

- It explains how people can use experience to make difficult decisions.

- It demonstrates that people can make effective decisions without using a rational choice strategy. (emphasis mine)