Gary Klein, et al, (Klein et al. n.d.)

Summary

Thoughts

The theory and concepts of data and frames make intuitive sense to me. Maybe I’ve heard about this theory already by other names? It’s nice to have a framework and terms to go with these concepts as well as a way of understanding differences between novices and experts.

Notes

In this chapter, we attempt to explain the nature of sensemaking [Sensemaking] activities. We define sensemaking as the deliberate effort to understand events. It is typically triggered by unexpected changes or other surprises that make us doubt our prior understanding. We also describe how these sensemaking activities can result in a faulty account of events. Our description incorporates several different aspects of sensemaking:

- The initial account people generate to explain events.

- The elaboration of that account.

- The questioning of that account in response to inconsistent data.

- Fixation on the initial account.

- Discovering inadequacies in the initial account.

- Comparison of alternative accounts.

- Reframing the initial account and replacing it with another.

- The deliberate construction of an account when none is automatically recognized.

[… See Examples 1 and 2 below]

As these examples show, sensemaking goes well beyond the comprehension of stimuli. The examples also show that sensemaking can be used for different functions.

- problem detection — to determine if the pattern was worth worrying about and monitoring more closely

- connecting the dots and making discoveries

- forming explanations, as when a physician diagnoses an illness or a mechanic figures out how a device works

- anticipatory thinking, to prevent potential accidents

- project future states in order to prepare for them

- find the levers — to figure out how to think and act in a situation, as when a project team tries to decide what type of projector to purchase and realizes that the decision is basically a trade-off between cost, size, and functionality

- see relationships, as when we use a map to understand where we are located

- problem identification, as when a physics student tries to find a means of depicting the variables in a homework problem in order to find a solution strategy.

Research into sensemaking should reflect these and other functions in order to provide a more comprehensive account.

[formatting mine]

Data-frame theory of sensemaking

The data–frame theory postulates that elements are explained when they are fitted into a structure that links them to other elements. We use the term frame to denote an explanatory structure that defines entities by describing their relationship to other entities. A frame can take the form of a story, explaining the chronology of events and the causal relationships between them; a map, explaining where we are by showing distances and directions to various landmarks and showing routes to destinations; a script, explaining our role or job as complementary to the roles or jobs of others; or a plan for describing a sequence of intended actions. Thus, a frame is a structure for accounting for the data and guiding the search for more data. It reflects a person’s compiled experiences.

People explore their environment by attending to a small portion of the available information. The data identify the relevant frame, and the frame determines which data are noticed. Neither of these comes first. The data elicit and help to construct the frame; the frame defines, connects, and filters the data. “The frame may be in error, but until feedback or some other form of information makes the error evident, the frame is the foundation for understanding the situation and for deciding what to do about it” (Beach, 1997, p. 24).

Sensemaking begins when someone experiences a surprise or perceives an inadequacy in the existing frame and the existing perception of relevant data. The active exploration proceeds in both directions, to improve or replace the frame and to obtain more relevant data. The active exploration of an environment, conducted for a purpose, reminds us that sensemaking is an active process and not the passive receipt and combination of messages.

The data–frame relationship is analogous to a hidden-figures task. People have trouble identifying the hidden figure until it is pointed out to them, and then they can’t not see it. Once the frame becomes clear, so do the data.

Assertions of the data-frame theory of sensemaking

Sensemaking is the process of fitting data into a frame and fitting a frame around the data

We distinguish between two entities: data and frames. Data are the interpreted signals of events; frames are the explanatory structures that account for the data. People react to data elements by trying to find or construct a story, script, a map, or some other type of structure to account for the data. At the same time, their repertoire of frames — explanatory structures — affects which data elements they consider and how they will interpret these data. We see sensemaking as the effort to balance these two entities — data and frames. If people notice data that do not fit into the frames they’ve been using, the surprise will often initiate sensemaking to modify the frame or replace it with a better one. Another reaction would be to use the frame to search for new data or to reclassify existing data, which in turn could result in a discovery of a better frame.

The “data” are inferred, using the frame, rather than being perceptual primitives

Data elements are not perfect representations of the world but are constructed — the way we construct memories rather than remembering all of the events that took place. Different people viewing the same events can perceive and recall different things depending on their goals and experiences. (See Medin, Lynch, Coley, & Atran, 1997, and Wisniewski & Medin, 1994, for discussions of the construction of cues and categories.) A fireground commander, an arson investigator, and an insurance agent will all be aware of different cues and cue patterns in viewing the same house on fire. […]

Because the little things we call “data” are actually abstractions from the environment, they can be distortions of reality. Feltovich, Spiro, and Coulson (1997) described the ways we simplify the world in trying to make sense of it:

- We define continuous processes as discrete steps

- We treat dynamic processes as static

- We treat simultaneous processes as sequential

- We treat complex systems as simple and direct causal mechanisms

- We separate processes that interact

- We treat conditional relationships as universals

- We treat heterogeneous components as homogeneous

- We treat irregular cases as regular ones

- We treat nonlinear functional relationships as linear

- We attend to surface elements rather than deep ones

- We converge on single interpretations rather than multiple interpretations

The frame is inferred from a few key anchors

When we encounter a new situation or a surprising turn of events, the initial one or two key data elements we experience sometimes serve as anchors for creating an understanding. These anchors elicit the initial frame, and we use that frame to search for more data elements.

[…]

Example 3 [below] shows the process of using anchors to select frames. The decision maker treated each data element as an anchor and used it to frame an explanation for an aviation accident. Each successive data element suggested a new frame, and the person moved from one frame to the next without missing a beat.

The inferences used in sensemaking rely on abductive reasoning as well as logical deduction

Our research with information operations specialists (Klein, Phillips, et al., 2003) found that they rely on abductive reasoning to a greater extent than following deductive logic. For example, they were more likely to speculate about causes, given effects, than they were to deduce effects from causes. If one event preceded another (simple correlation) they speculated that the first event might have caused the second. They were actively searching for frames to connect the messages they were given.

Abductive reasoning (e.g., Peirce, 1903) is reasoning to the best explanation. Josephson and Josephson (1994, p. 5) have described a paradigm case for abductive reasoning:

- D is a collection of data (facts, observations, and givens).

- H explains D (would, if true, explain D).

- No other hypothesis can explain D as well as H does.

- Therefore, H is probably true.

In other words, if the match between a set of data and a frame is more plausible than the match to any other frame, we accept the first frame as the likely explanation. This is not deductive reasoning, but a form of reasoning that enables us to make sense of uncertain events. It is also a form of reasoning that permits us to generate new hypotheses, based on the frame we adopt.

[…]

[…] People are explanation machines. People will employ whatever tactics are available to help them find connections and identify anchors.

Sensemaking usually ceases when the data and frame are brought into congruence

Sensemaking is a Satisficing activity.

Our observations of sensemaking suggest that, as a deliberate activity, it continues as long as key data elements remain unexplained or key components of a frame remain ambiguous. Once the relevant data are readily accounted for, and the frame seems reasonably valid and specified, the motivation behind sensemaking is diminished. Thus, sensemaking has a stopping point — it is not an endless effort to grind out more inferences. We note that sensemaking may continue if the potential benefits of further exploration are sufficiently strong. Example 2 shows how the brigadier general continued to make discoveries by further exploring the scene in front of him.

Experts reason the same way as novices, but have a richer repertoire of frames

See Cedric Chin | Expertise Is ‘Just’ Pattern Matching, Recognition-primed decision.

Klein et al. (2002) reported that expert information operations specialists performed at a much higher level than novices, but both groups employed the same types of logical and abductive inferencing. This finding is in accord with the literature (e.g., Barrows, Feightner, Neufeld, & Norman, 1978; Elstein, Shulman, & Sprafka, 1978; Simon, 1973) reporting that experts and novices showed no differences in their reasoning processes.

Klein et al. (2002) found that expert and novice information operations specialists both tried to infer cause–effect connections when presented with information operations scenarios. They both tried to infer effects, although the experts were more capable of doing this. They both tried to infer causes from effects. They were both aware of multiple causes, and neither were particularly sensitive to instances when an expected effect did not occur. The experts have the benefit of more knowledge and richer mental models. But in looking at these data and in watching the active connection building of the novices, we did not find that the experts were using different sensemaking strategies from the novices (with a few exceptions, noted later). This finding suggests that little is to be gained by trying to teach novices to think like experts. Novices are already trying to make connections. They just have a limited knowledge base from which to work.

[…]

Although the experts and novices showed the same types of reasoning strategies, the experts had the advantage of a much stronger understanding of the situations. Their mental models were richer in terms of having greater variety, finer differentiation, and more comprehensive coverage of phenomena. Their comments were deeper, more plausible, showed a greater sensitivity to context, and were more insightful.

The mechanism of generating inferences was the same for experts and novices, but the nature of the experts’ inferences was much more interesting. For example, one of the three scenarios we used, “Rebuilding the Schools,” included the message, “An intel report designates specific patrols that are now being targeted in the eastern Republica Srpska. A group that contains at least three known agitators is targeting the U.S. afternoon Milici patrol for tomorrow and the IPTF patrol for the next day.” One of the experts commented that this was very serious, and generated action items to find out why the posture of the agitators had shifted toward violence in this way. He also speculated on ways to manipulate the local chief of police. The second expert saw this as an opportunity to identify and strike at the violent agitators. In contrast, one of the novices commented, “There is a group targeting U.S. afternoon patrols — then move the patrols.” The other novice stated, “The targeting of the patrols — what that means is not clear to me. Is there general harassment or actions in the past on what has happened with the patrols?”

Generally, the novices were less certain about the relevance of messages, and were more likely to interpret messages that were noise in the scenario as important signals. Thus, in “Rebuilding the Schools,” another message stated that three teenagers were found in a car with contraband cigarettes. One expert commented, “Business as usual.” The second expert commented, “Don’t care. You could spend a lot of resources on controlled cigarettes — and why? Unless there is a larger issue, let it go.” In contrast, the novices became concerned about this transgression. One wondered if the teenagers were part of a general smuggling gang. Another wanted more data about where the cigarettes came from. A third novice wanted to know what type of suspicious behavior had gotten the teenagers pulled over.

Sensemaking is used to achieve a functional understanding

In many settings, experienced practitioners want a functional understanding as well as an abstract understanding. They want to know what to do in a situation. In some domains, an abstract understanding is sufficient for experts. Scientists are usually content with gaining an abstract understanding of events and domains because they rarely are called on to act on this understanding. Intelligence officers can seek an abstract understanding of an adversary if they cannot anticipate how their findings will be applied during military missions. In other domains, experts need a functional understanding along with an abstract understanding. Weather forecasters can seek a functional understanding of a weather system if they have to issue alerts or recommend emergency evacuations in the face of a threatening storm.

[…] For the three scenarios we used, the experts were almost three times as likely to make comments about actions that should be taken, compared to the novices. The novices we studied averaged 1.5 action suggestions per scenario and the experts averaged 4.4 action suggestions per scenario.

[…]

Charness (1979) reported the results of a cognitive task analysis conducted with bridge players. The sensemaking of the skilled bridge players was based on what they could or could not achieve with a hand — the affordances of the hand they were dealt. In contrast, the novices interpreted bridge hands according to more abstract features such as the number of points in the hand.

People primarily rely on just-in-time mental models

We distinguish between comprehensive mental models and just-in-time (JIT) mental models. A comprehensive mental model captures the essential relationships. An automobile mechanic has a comprehensive mental model of the braking system of a car. An information technology specialist has a comprehensive mental model of the operating system of a computer. In contrast, most of us have only incomplete ideas of these systems. We have some knowledge of the components, and of the basic causal relationships, but there are large gaps in our understanding. If we have to do our own troubleshooting, we have to go beyond our limited knowledge, make some inferences, and cobble together a notion of what is going on — a JIT mental model. We occasionally find that even the specialists to whom we turn don’t have truly complete mental models, as when a mechanic fails to diagnose and repair an unusual problem or an information technology specialist needs to consult with the manufacturer to figure out why a computer is behaving so strangely.

The concept of JIT is not intended to convey time pressure. It refers to the construction of a mental model at the time it is needed, rather than calling forth comprehensive mental models that already have been developed. In most of the incidents we examined, the decision makers did not have a full mental model of the situation or the phenomenon they needed to understand. For example, one of the scenarios we used with information operations specialists contained three critical messages that were embedded in a number of other filler messages: The sewage system in a refugee camp was malfunctioning, refugees were moving from this camp to a second camp, and an outbreak of cholera was reported in the second camp. We believed that the model of events would be clear — the refugees were getting sick with cholera in the first camp because of the sewage problem and spreading it to the second camp. However, we discovered that none of the information operations specialists, even the experts, understood how cholera is transmitted. Therefore, none of them automatically connected the dots when they read the different messages. A few of the specialists, primarily the experts, did manage to figure out the connection as we presented more pointed clues. They used what they knew about diseases to speculate about causes, and eventually realized what was triggering the cholera outbreak in the second camp.

We suggest that people primarily rely on JIT mental models — building on the local cause–effect connections they know about, instead of having comprehensive mental models of the workings of an entire system. These JIT mental models are constructions, using fragmentary knowledge from long-term memory to build explanations in a context. Just as our memories are partial constructions, using fragments of recall together with beliefs, rules, and other bases of inference, we are claiming that most of our mental models are constructed as the situation warrants. Experienced decision makers have learned a great many simple causal connections, “A” leads to “B,” along with other relationships. When events occur that roughly correspond to “A” and “B,” experienced decision makers can see the connection and reason about the causal relationship. This inference can become an anchor in its own right, if it is sufficiently relevant to the task at hand. And it can lead to a chain of inferences, “A” to “B,” “B” to “C,” and so on.

We believe that in many domains, people do not have comprehensive mental models but can still perform effectively. The fragmentary mental models of experts are more complete than those of novices.

Sensemaking takes different forms, each with its own dynamics

In studying the process of sensemaking in information operations specialists and in other domains, we found different types. If we ignore these types, our account of sensemaking will be too general to be useful. The next section describes the alternative ways that sensemaking can take place. standing. Any cognitive activity, no matter how deliberate, will be influenced by unconscious processes. The range between conscious and unconscious processes can be thought of as a continuum, with pattern matching at one end and comparing different frames at the other end. The blending of conscious and automatic processes varies from one end of the continuum to the other.

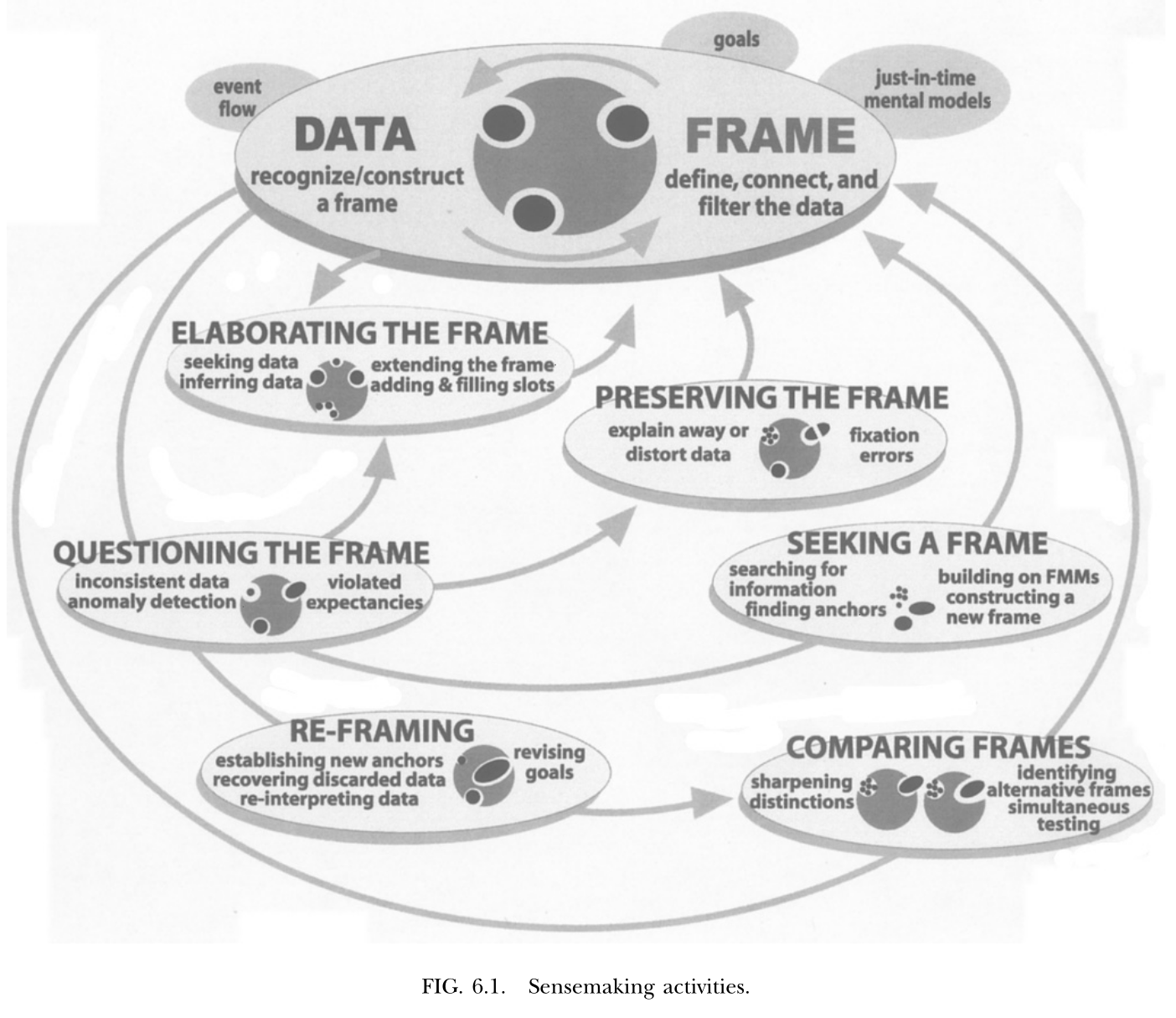

To illustrate this continuum, consider the recognition-primed decision (RPD) [Recognition-primed decision] model presented by Klein (1998). Level 1 of the RPD model describes a form of decision making that is based on pattern matching and the recognition of typical situations. The initial frame recognition defines cues (the pertinent data), goals, and expectancies. This level of the RPD model corresponds to the basic data–frame connection shown at the top center of Figure 6.1, and in the icon at the beginning of this section. We do not view this recognitional match as an instance of sensemaking.

Klein also described Level 2 of the RPD model in which the decision maker does deliberate about the nature of the situation, sometimes constructing stories to try to account for the observed data. At Level 2, the decision maker is engaging in the different forms of sensemaking. The data–frame theory is an extension of the story-building strategy described in this Level 2.

The initial frame used to explain the data can have important consequences. Thus, a fireground commander has stated that the way an onscene commander sizes up the situation in the first 5 minutes determines how the fire will be fought for the next 5 hours.

The forms of sensemaking

Also see Example 6.

Sensemaking attempts to connect data and frame

The specific frame a person uses depends on the data or information that are available and also on the person’s goals, the repertoire of the person’s frames, and the person’s stance (e.g., current workload, fatigue level, and commitment to an activity).

We view sensemaking as a volitional process, rather than an unconscious one. In many instances the automatic recognition of how to frame a set of events will not require a person to engage in deliberate sensemaking. The matching of data and frame is often achieved preconsciously, through pattern matching and recognition.

We are not dismissing unconscious processes as concomitants of sensemaking. Rather, we are directing our investigation into incidents where deliberate reasoning is employed to achieve some level of under-

Elaborating the frame

As more is learned about the environment, people will extend and elaborate the frame they are using, but will not seek to replace it as long as no surprises or anomalies emerge. They add more details, fill in slots, and so forth.

Questioning the frame

Questioning begins when we are surprised — when we have to consider data that are inconsistent with the frame we are using. This is a different activity than elaborating the frame. Lanir (1991) has used the term “fundamental surprise” to describe situations in which we realize we may have to replace a frame on which we had been depending. […]

In this aspect of sensemaking, we may not know if the frame is incorrect, if the situation has changed, or if the inconsistent data are inaccurate. At this point, we just realize that some of the data do not match the frame. Frames provide people with expectations; when the expectations are violated, people may start to question the accuracy of the frame.

Weick (1995) postulated that sensemaking is often initiated by a surprise — the breakdown in expectations as when unexpected events occur or expected events fail to occur. Our research findings support this assertion. Thus, in the navigation incidents we studied, we found that people who got lost might continue for a long time until they experienced a framebreaker, a “moment of untruth,” that knocked them out of their existing beliefs and violated their expectancies.

Even in the navigation incidents we studied, people were often trying to make sense of events even before they encountered a frame breaker. They actively preserved and elaborated their frames until they realized that their frames were flawed. Emotional reactions are also important for initiating sensemaking, by generating a feeling of uncertainty or of distress caused by loss of confidence in a frame.

Problem detection (e.g., Klein, Pliske, Crandall, & Woods, in press) is a form of sensemaking in which a person begins to question the frame. However, a person will not start to question a frame simply as a result of receiving data that do not conform to the frame. For example, Feltovich et al. (1984) found that experts in pediatric cardiology had more differentiated frames than novices, letting them be more precise about expectations. Novices were fuzzy about what to expect when they looked at test results, and therefore were less likely to notice when expectancies were violated. As a result, when Feltovich et al. presented a “garden path” scenario (one that suggested an interpretation that turned out to be inaccurate), novices went down the garden path but experts broke free. The experts quickly noticed that the data were not aligning with the initial understanding.

Example 4 [below] describes a fire captain questioning his frame for the progression of a fire involving a laundry chute (taken from Klein, 1998). He realizes that the data do not match his frame when he sees flames rolling along the ceiling of the fourth-floor landing; at this point he recognizes the fire is much more involved than he originally expected, and he is able to quickly adapt his strategies to accommodate the seriousness of the fire.

Preserving the frame

We typically preserve a frame by explaining away the data that do not match the frame. Sometimes, we are well-advised to discard unreliable or transient data. But when the inconsistent data are indicators that the explanation may be faulty, it is a mistake to ignore and discard these data. Vaughan (1996) describes how organizations engage in a routinization of deviance, as they explain away anomalies and in time come to see them as familiar and not particularly threatening. Our account of preserving a frame may help to describe how routinization of deviance is sustained.

Feltovich, Coulson, and Spiro (2001) have cataloged a set of “knowledge shields” [Knowledge shields] that cardiologists use to preserve a frame in the face of countervailing evidence. […]

[…] It is not as if people seek to fixate. Rather, people are skilled at forming explanations. And they are skilled at explaining how inconvenient data may have arisen accidentally — using the knowledge shields […]

Comparing multiple frames

We sometimes need to deliberately compare different frames to judge what is going on.

For example, in reviewing incidents from a study of nurses in an NICU (Crandall & Gamblian, 1991), we found several cases where the nurses gathered evidence in support of one frame — that the neonate was making a good recovery — while at the same time elaborated a second, opposing frame — that the neonate was developing sepsis. [See Example 5]

In some of our incident analyses, we have found that people were tracking up to three frames simultaneously. We speculate that this may be an upper limit; people may track two to three frames simultaneously, but rarely more than three.

In their research on pediatric cardiologists, Feltovich et al. (1984) found that when the experts broke free of the fixation imposed by a garden path scenario, they would identify one, two, or even three alternative frames. The experts deliberately selected frames that would sharpen the distinctions that were relevant. They identified a cluster of diseases that shared many symptoms in order to make fine-grained diagnoses. Feltovich et al. referred to this strategy as using a “logical competitor set” (LCS) as a means of pinpointing critical details. To Feltovich et al., the LCS is an interconnected memory unit that can be considered a kind of category. Activation of one member of the LCS will activate the full set because these are the similar cardiac conditions that have to be contrasted. Depending on the demands of the task, the decision maker may set out to test all the members of the set simultaneously, or may test only the most likely member. Rudolph (2003) sees this strategy as a means of achieving a differential diagnosis. The anesthesiologists in her study changed the way they sought information — their search strategies became more directed and efficient when they could work from a set of related and competing frames.

We also speculate that if a data element is used as an anchor in one frame, it will be difficult to use it in a second, competing frame. The rival uses of the same anchor may create conceptual strain, and this would limit a person’s ability to compare frames.

Reframing

In reframing, we are not simply accumulating inconsistencies and contrary evidence. We need the replacement frame to guide the way we search for and define cues, and we need these cues to suggest the replacement frame. Both processes happen simultaneously.

[…]

Duncker (1945) introduced the concept that gaining insight into the solution to a problem may require reframing or reformulating the way the problem is understood. Duncker studied the way subjects approached the now-classic “radiation problem” (how to use radiation to destroy a tumor without damaging the healthy tissue surrounding the tumor). As long as the problem was stated in that form, subjects had difficulty finding a solution. Some subjects were able to reframe the problem, from “how to use radiation to treat a tumor without destroying healthy tissue” to “how to minimize the intensity of the radiation except at the site of the tumor.” This new frame enabled subjects to generate a solution of aiming weak radiation beams that converged on the tumor.

Seeking a frame

We may deliberately try to find a frame when confronted with data that just do not make sense, or when a frame is questioned and is obviously inadequate. Sometimes, we can replace one frame with another, but at other times we have to try to find or construct a frame. We may look for analogies [Reasoning from analogies] and also search for more data in order to find anchors that can be used to construct a new frame.

Potential applications of the data-frame theory

Decision support systems

In designing DSSs, one of the lessons from the literature is that more data does not necessarily lead to more accurate explanations and predictions. Weick (1995) criticized the information-processing metaphor for viewing sensemaking and related problems as settings where people need more information. Weick argued that a central problem requiring sensemaking is that there are too many potential meanings, not too few — equivocality rather than uncertainty. For Weick, resolving equivocality requires values, priorities, and clarity about preferences, rather than more information.

Heuer (1999) made a similar point, arguing that intelligence analysts need help in evaluating and interpreting data, not in acquiring more and more data. The research shows that accuracy increases with data elements up to a point (perhaps 8–10 data elements) and then asymptotes while confidence continues to increase […]

[…]

We can offer some guidance for the field of DSSs:

- Attempts to improve judgment and decision quality by increasing the amount of data are unlikely to be as effective as supports to the evaluation of data. Efforts to increase information rate can actually interfere with skilled performance.

- The DSS should not be restricted to logical inferences, because of the importance of abductive inferences.

- The progression of data-information-knowledge-understanding that is shown as a rationale for decision support systems is misleading. It enshrines the information-processing approach to sensemaking, and runs counter to an ecological approach that asserts that the data themselves need to be constructed.

- Data fusion algorithms pose opportunities to reduce information overload, but also pose challenges to sensemaking if the logical bases of the algorithms are underspecified.

- Given the limited number of anchors that are typically used, people may benefit from a DSS that helps them track the available anchors.

- DSSs may be evaluated by applying metrics such as the time needed to catch inconsistencies inserted into scenarios and the time and effort needed to detect faulty data fusion.

Training programs

The concept of sensemaking also appears to be relevant to the development of training programs. For example, one piece of advice that is often given is that decision makers can reduce fixation errors by avoiding early adoption of a hypothesis. But the data–frame theory regards early commitment to a hypothesis as inevitable and advantageous. Early commitment, the rapid recognition of a frame, permits more efficient information gathering and more specific expectancies that can be violated by anomalies, permitting adjustment and reframing. This claim can be tested by encouraging subjects to delay their interpretation, to see if that improves or hinders performance. It can be falsified by finding cases where the domain practitioner does not enact “early” recognition of a frame.

A second implication of sensemaking is the use of feedback in training. Practice without feedback is not likely to result in effective training. But it is not trivial to provide feedback. Outcome feedback is not as useful as process feedback (Salas, Wilson, Burke, & Bowers, 2002), because knowing that performance was inadequate is not as valuable as diagnosing what needs to be changed. However, neither outcome nor process feedback is straightforward. Trainees have to make sense of the feedback.

Feedback does not inevitably lead to better frames. The frames determine the way feedback is understood. Similarly, process feedback is best understood when a person already has a good mental model of how to perform the task. A person with a poor mental model can misinterpret process feedback.

A third issue that is relevant to training concerns the so-called confirmation bias. The decision research literature (Mynatt, Doherty, & Tweney, 1977; Wason, 1960) suggests that people are more inclined to look for and take notice of information that confirms a view than information that disconfirms it.

In contrast, we assert that people are using frames, not merely trying to confirm hypotheses. In natural settings, skilled decision makers shift into an active mode of elaborating the competing frame once they detect the possibility that their frame is inaccurate. This tactic is shown in the earlier NICU Example 5 where the nurse tracked two frames. A person uses an initial frame (hypothesis) as a guide in acquiring more information, and, typically, that information will be consistent with the frame. Furthermore, skilled decision makers such as expert forecasters have learned to seek disconfirming evidence where appropriate.

It is not trivial to search for disconfirming information — it may require the activation of a competing frame. Patterson, Woods, Sarter, and WattsPerotti (1998), studying intelligence analysts who reviewed articles in the open literature, found that if the initial articles were misleading, the rest of the analyses would often be distorted because subsequent searches, and their reviews were conditioned by the initial frame formed from the first articles. The initial anchors affect the frame that is adopted, and that frame guides information seeking. What may look like a confirmation bias may simply be the use of a frame to guide information seeking. One need not think of it as a bias.

Accordingly, we offer the following recommendations:

- We suggest that training programs advocating a delayed commitment to a frame are unrealistic. Instead, training is needed in noticing anomalies and diagnosing them.

- Training may be useful in helping people “get found.” For example, helicopter pilots are taught to navigate from one waypoint to another. However, if the helicopters are exposed to antiair attacks, they will typically take violent evasive maneuvers to avoid the threat. These maneuvers not infrequently leave the pilots disoriented. Training might be helpful in developing problem-solving routines for getting found once the pilots are seriously lost.

- Training to expand a repertoire of causal relationships may be more helpful than teaching comprehensive mental models.

- Training in generic sensemaking does not appear to be feasible. We have not seen evidence for a general sensemaking skill. Some of the incidents we have collected do suggest differences in an “adaptive mind-set” of actively looking to make sense of events, as in Example 2. It may be possible to develop and expand this type of attitude.

- Training may be better aimed at key aspects responsible for effective sensemaking, such as increasing the range and richness of frames. For example, Phillips et al. (2003) achieved a significant improvement in sensemaking for Marine officers trained with tactical decision games that were carefully designed to improve the richness of mental models and frames.

- Training may be enhanced by verifying that feedback is appropriately presented and understood.

- Training may also be useful for helping people to manage their attention to become less vulnerable to distractions. Dismukes (1998) described how interruptions can result in aviation accidents. Jones and Endsley (1995, 2000) reviewed aviation records and found that many of the errors in Endsley’s (1995) Level 1 situation awareness (perception of events) were compounded by ineffective attention management—failure to monitor critical data, and misperceptions and memory loss due to distractions and/ or high workload. The management of attention would seem to depend on the way frames are activated and prioritized.

- Training scenarios can be developed for all of the sensemaking activities shown in Figure 6.1: elaborating a frame, questioning a frame, evaluating a frame, comparing alternative frames, reframing a situation, and seeking anchors in order to generate a useful frame.

- Metrics for sensemaking training might include the time and accuracy in detecting anomalies, the degree of concordance with subject-matter expert assessments, and the time and success in recovering from a mistaken interpretation of a situation.

Testable aspects of the data-frame theory

Now that we have described the data–frame theory, we want to consider ways of testing it. Based on the implications described previously, and our literature review, we have identified several hypotheses about the data– frame theory:

- We hypothesize that frames are evoked/constructed using only three or four anchors.

- We hypothesize that if someone uses a data element as an anchor for one frame, it will be difficult to use that same anchor as a part of a second, competing frame.

- We hypothesize that the quality of the initial frame considered will be better than chance—that people identify frames using experience, rather than randomly. Based on past research on recognitional decision making, we assert that the greater the experience level, the greater the improvement over chance of the frame initially identified.

- We hypothesize that introducing a corrupted, inaccurate anchor early in the message stream will have a correspondingly greater negative effect on sensemaking accuracy than introducing it later in the sequence (see Patterson et al., 1998).

- We hypothesize that increased information and anchors will have a nonlinear relationship to performance, first increasing it, then plateauing, and then in some cases, decreasing. This claim is based on research literature cited previously, and also on the basic data–frame concept and the consequences of adding too many data without a corresponding way to frame them.

- We hypothesize that experts and novices will show similar reasoning strategies when trying to make inferences from data.

- We hypothesize that methods designed to prevent premature commitment to a frame (e.g., the recognition/metacognition approach of Cohen, Adelman, Tolcott, Bresnick, & Marvin, 1992) will degrade performance under conditions where active attention management is needed (using frames) and where people have difficulty finding useful frames. The findings reported by Rudolph (2003) suggest that failure to achieve early commitment to a frame can actually promote fixation because commitment to a frame is needed to generate expectancies (and to support the recognition of anomaly) and to conduct effective tests. The data–frame concept is that a frame is needed to efficiently and effectively understand data, and that attempting to review data without introducing frames is unrealistic and unproductive.

- We hypothesize that people can track up to three frames at a time, but that performance may degrade if more than three frames must be simultaneously considered. We also speculate that individual differences (e.g., tolerance for ambiguity, need for cognition) should affect sensemaking performance, and that this can be a fruitful line of research. Similarly, cultural differences, such as holistic versus analytical perspectives, should affect sensemaking (Nisbett, 2003). Furthermore, it may be possible to establish priming techniques to elicit frames and to demonstrate this elicitation in the sensemaking and information management activities shown by subjects.

Summary

Sensemaking is the deliberate effort to understand events. It serves a variety of functions, such as explaining anomalies, anticipating difficulties, detecting problems, guiding information search, and taking effective action. We have presented a data–frame theory of the process of sensemaking in natural settings.

The theory contains a number of assertions.

The theory posits that the interaction between the data and the frame is a central feature of sensemaking. The data, along with the goals, expertise, and stance of the sensemaker, combine to generate a relevant frame. The frame subsequently shapes which data from the environment will be recognized as pertinent, how the data will be interpreted, and what role they will play when incorporated into the evolving frame. Our view of the data–frame relationship mirrors Neisser’s (1976) cyclical account of perception, in that available information, or data, modifies one’s schema, or frame, of the present environment, which in turn directs one’s exploration and/or sampling of that environment. The data are used to select and alter the frame. The frame is used to select and configure the data. In this manner, the frame and the data work in concert to generate an explanation. The implication of this continuous, two-way, causal interaction is that both sensemaking and data exploration suffer when the frame is inadequate.

Our observations in several domains suggest that people select frames based on a small number of anchors—highly salient data elements. The initial few anchors seem to determine the type of explanatory account that is formed, with no more than three to four anchors active at any point in time.

Our research is consistent with prior work (Barrows et al., 1978; Chase & Simon, 1973; Elstein, 1989) showing that expert–novice differences in sensemaking performance are not due to superior reasoning on the part of the expert or mastery of advanced reasoning strategies, but rather to the quality of the frame that is brought to bear. Experts have more factual knowledge about their domain, have built up more experiences, and have more knowledge about cause-and-effect relationships.

Experts are more likely to generate a good explanation of the situation than novices because their frame enables them to select the right data from the environment, interpret them more accurately, and see more pertinent patterns and connections in the data stream.

We suggest that people more often construct JIT mental models from available knowledge than draw on comprehensive mental models. We have not found evidence that people often form comprehensive mental models. Instead, people rely on JIT models, constructed from fragments, in a way that is analogous to the construction of memory. In complex and open systems, a comprehensive mental model is unrealistic.

There is some evidence that in domains dealing with closed systems, such as medicine (i.e., the human body can be considered a roughly closed system), an expert can plausibly develop an adequately comprehensive mental model for some medical conditions. However, most people and even most experts rely on fragments of local cause–effect connections, rules of thumb, patterns of cues, and other linkages and relationships between cues and information to guide the sensemaking process (and indeed other high-level cognitive processes).

The concept of JIT mental models is interesting for several reasons. We believe that the fragmentary knowledge (e.g., causal relationships, rules, principles) representing one domain can be applied to a sensemaking activity in a separate domain. If people have worked out complex and comprehensive mental models in a domain, they will have difficulty in generalizing this knowledge to another domain, whereas the generalization of fragmentary knowledge is much easier. Fragmentary knowledge contributes to the frame that is constructed by the sensemaker; fragmentary knowledge therefore helps to guide the selection and interpretation of data. We do not have to limit our study of mental models to the static constructs and beliefs that people hold; we can also study the process of compiling JIT mental models from a person’s knowledge base.

The data–frame account of sensemaking is different from an information-processing description of generating inferences on data elements. Sensemaking is motivated by the person’s goals and by the need to balance the data with the frame—a person experiences confusion in having to consider data that appear relevant and yet are not integrated. Successful sensemaking achieves a mental balance by fitting data into a well-framed relationship with other data. This balance will be temporary because dynamic conditions continually alter the landscape. Nevertheless, the balance, when achieved, is emotionally satisfying in itself. People do not merely churn out inferences. They are actively trying to experience a match, however fleeting, between data and frame.

[formatting mine]

Example 1: The ominous airplanes

Major A. S. discussed an incident that occurred soon after 9/11 in which he was able to determine the nature of overflight activity around nuclear power plants and weapons facilities. This incident occurred while he was an analyst. He noticed that there had been increased reports in counterintelligence outlets of overflight incidents around nuclear power plants and weapons facilities. At that time, all nuclear power plants and weapons facilities were “temporary restricted flight” zones. So this meant there were suddenly a number of reports of small, low-flying planes around these facilities. At face value it appeared that this constituted a terrorist threat — that “bad guys” had suddenly increased their surveillance activities. There had not been any reports of this activity prior to 9/11 (but there had been no temporary flight restrictions before 9/11 either).

Major A. S. obtained access to the Al Qaeda tactics manual, which instructed Al Qaeda members not to bring attention to themselves. This piece of information helped him to begin to form the hypothesis that these incidents were bogus — “It was a gut feeling, it just didn’t sit right. If I was a terrorist I wouldn’t be doing this.”

He recalled thinking to himself, “If I was trying to do surveillance how would I do it?” From the Al Qaeda manual, he knew they wouldn’t break the rules, which to him meant that they wouldn’t break any of the flight rules. He asked himself, “If I’m a terrorist doing surveillance on a potential target, how do I act?” He couldn’t put together a sensible story that had a terrorist doing anything as blatant as overflights in an air traffic restricted area.

He thought about who might do that, and kept coming back to the overflights as some sort of mistake or blunder. That suggested student pilots to him because “basically, they are idiots.”

He was an experienced pilot. He knew that during training, it was absolutely standard for pilots to be instructed that if they got lost, the first thing they should look for were nuclear power plants. He told us that “an entire generation of pilots” had been given this specific instruction when learning to fly. Because they are so easily sighted, and are easily recognized landmarks, nuclear power plants are very useful for getting one’s bearings. He also knew that during pilot training the visual flight rules would instruct students to fly east to west and low — about 1,500 feet. Basically students would fly low patterns, from east to west, from airport to airport.

It took Major A. S. about 3 weeks to do his assessment. He found all relevant message traffic by searching databases for about 3 days. He picked the three geographic areas with the highest number of reports and focused on those. He developed overlays to show where airports were located and the different flight routes between them. In all three cases, the “temporary restricted flight” zones (and the nuclear power plants) happened to fall along a vector with an airport on either end. This added support to his hypothesis that the overflights were student pilots, lost and using the nuclear power plants to reorient, just as they had been told to do.

He also checked to see if any of the pilots of the flights that had been cited over nuclear plants or weapons facilities were interviewed by the FBI. In the message traffic, he discovered that about 10% to 15% of these pilots had been detained, but none had panned out as being “nefarious pilots.”

With this information, Major A. S. settled on an answer to his question about who would break the rules: student pilots. The students were probably following visual flight rules, not any sort of flight plan. That is, they were flying by looking out the window and navigating.

This instance of sensemaking was triggered by the detection of an anomaly. But we engage in sensemaking even without surprises, simply to extend our grasp of what is going on.

Example 2: The reconnaissance team

During a Marine Corps exercise, a reconnaissance team leader and his team were positioned overlooking a vast area of desert. The fire team leader, a young sergeant, viewed the desert terrain carefully and observed an enemy tank move along a trail and then take cover. He sent this situation report to headquarters. However, a brigadier general, experienced in desert-mechanized operations, had arranged to go into the field as an observer. He also spotted the enemy tank. But he knew that tanks tend not to operate alone. Therefore, based on the position of that one tank, he focused on likely overwatch positions and found another tank. Based on the section’s position and his understanding of the terrain, he looked at likely positions for another section and found a well-camouflaged second section. He repeated this process to locate the remaining elements of a tank company that was well-camouflaged and blocking a key choke point in the desert. The size and position of the force suggested that there might be other higher and supporting elements in the area, and so he again looked at likely positions for command and logistics elements. He soon spotted an otherwise superbly camouflaged logistics command post. In short, the brigadier general was able to see and understand and make more sense of the situation than the sergeant. He had much more experience, and he was able to develop a fuller picture rather than record discrete events that he noticed.

Example 3: The investigation of a helicopter accident

An accident happened during an Army training exercise. Two helicopters collided. Everyone in one helicopter died and everyone in the other helicopter survived. Our informant, Captain B., was on the battalion staff at the time.

Immediately after the accident, Captain B. suspected that because this was a night mission there could have been some complications due to flying with night-vision goggles that led one helicopter to drift into the other.

Then Captain B. found out that weather had been bad during the exercise, and he thought that was probably the cause of the accident; perhaps they had flown into some clouds at night.

Then Captain B. learned that there was a sling on one of the crashed helicopters, and that this aircraft had been in the rear of the formation. He also found out that an alternate route had been used, and that weather wasn’t a factor because they were flying below the clouds when the accident happened. So Captain B. believed that the last helicopter couldn’t slow down properly because of the sling. The weight of the sling would make it harder to stop to avoid running into another aircraft. He also briefly suspected that pilot experience was a contributing factor, because they should have understood the risks better and kept better distance between aircraft, but he dismissed this idea because he found out that although the lead pilot hadn’t flown much recently, the copilot was very experienced. But Captain B. was puzzled about why the sling-loaded helicopter would have been in trail. It should have been in the lead because it was less agile than the others. Captain B. was also puzzled about the route — the entire formation had to make a big U-turn before landing and this might have been a factor too. So this story, though much different than the first ones, still had some gaps.

Finally, Captain B. found out that the group had not rehearsed the alternate route. The initial route was to fly straight in, with the sling-loaded helicopter in the lead. And that worked well because the sling load had to be delivered in the far end of the landing zone. But because of a shift in the wind direction, they had to shift the landing approach to do a U-turn. When they shifted the landing approach, the sling load had to be put in the back of the formation so that the load could be dropped off in the same place. When the lead helicopter came in fast and then went into the U-turn, the next two helicopters diverted because they could not execute the turn safely at those speeds and were afraid to slow down because the sling-loaded helicopter was right behind them. The sling-loaded helicopter continued with the maneuver and collided with the lead helicopter.

At first, Captain B. had a single datum, the fact that the accident took place at night. He used this as an anchor to construct a likely scenario. Then he learned about the bad weather, and used this fact to anchor an alternate and more plausible explanation.

Next he learned about the sling load, and fastened on this as an anchor because sling loads are so dangerous. The weather and nighttime conditions may still have been factors, but they did not anchor the new explanation, which centered around the problem of maneuvering with a sling load. Captain B.’s previous explanations faded away. Even so, Captain B. knew his explanation was incomplete, because a key datum was inconsistent — why was the helicopter with the sling load placed in the back of the formation?

Eventually, he compiled the anchors: helicopter with a sling load, shift in wind direction, shift to a riskier mission formation, unexpected difficulty of executing the U-turn. Now he had the story of the accident. He also had other pieces of information that contributed, such as time pressure that precluded practicing the new formation, and command failure in approving the risky mission.

Example 4: The laundry chute fire

A civilian call came in about 2030 hours that there was a fire in the basement of an apartment complex. Arriving at the scene of the call about 5 minutes later, Captain L. immediately radioed to the dispatcher that the structure was a four-story brick building, “nothing showing,” meaning no smoke or flames were apparent. He was familiar with this type of apartment building structure, so he and his driver went around the side of the building to gain access to the basement through one of the side stairwells located to either side of the building. Captain L. saw immediately that the clothes chute was the source of the fire.

Looking up the chute, which ran to the top floor, Captain L. could see nothing but smoke and flames. The duct was constructed of thin metal but with a surrounding wooden skirt throughout its length. Visibility was poor because of the engulfing flames, hampering the initial appraisal of the amount of involvement. Nevertheless, on the assumption that the civilian call came close in time to the start of the fire and that the firefighters’ response time was quick, Captain L. instantly assessed the point of attack to be the second-floor clothes chute access point.

Captain L. told the lieutenant in charge of the first arriving crew to take a line into the building. Three crews were sent upstairs, to the first, second, and third floors, and each reported back that the fire had already spread past them.

Captain L. made his way to the front of the building. Unexpectedly, he saw flames rolling along the ceiling of the fourth-floor landing of the glass encased front stairwell external to the building. Immediately recognizing that the fire must be quite involved, Captain L. switched his strategy to protecting the front egress for the now prime objective of search and rescue (S/R) operations. He quickly dispatched his truck crew to do S/R on the fourth floor and then radioed for a “triple two” alarm at this location to get the additional manpower to evacuate the entire building and fight this new front. Seven minutes had now elapsed since the first call.

On arrival, the new units were ordered to protect the front staircase, lay lines to the fourth floor to push the blaze back down the hall, and aid in S/ R of the entire building. Approximately 20 people were eventually evacuated, and total time to containment was about an hour.

Example 5: Comparison of frames in an NICU

This baby was my primary; I knew the baby and I knew how she normally acted. Generally she was very alert, was on feedings, and was off IVs. Her lab work on that particular morning looked very good. She was progressing extremely well and hadn’t had any of the setbacks that many other preemies have. She typically had numerous apnea episodes and then bradys, but we could easily stimulate her to end these episodes. At 2:30 her mother came in to hold her and I noticed that she wasn’t as responsive to her mother as she normally was. She just lay there and half looked at her. When we lifted her arm it fell right back down in the bed and she had no resistance to being handled. This limpness was very unusual for her.

On this day, the monitors were fine, her blood pressure was fine, and she was tolerating feedings all right. There was nothing to suggest that anything was wrong except that I knew the baby and I knew that she wasn’t acting normally. At about 3:30 her color started to change. Her skin was not its normal pink color and she had blue rings around her eyes. During the shift she seemed to get progressively grayer. Then at about 4:00, when I was turning her feeding back on, I found that there was a large residual of food in her stomach. I thought maybe it was because her mother had been holding her and the feeding just hadn’t settled as well. By 5:00 I had a baby who was gray and had blue rings around her eyes. She was having more and more episodes of apnea and bradys; normally she wouldn’t have any bradys when her mom was holding her. Still, her blood pressure hung in there. Her temperature was just a little bit cooler than normal. Her abdomen was a little more distended, up 2 cm from early in the morning, and there was more residual in her stomach. This was a baby who usually had no residual and all of a sudden she had 5 cc to 9 cc. We gave her suppositories thinking maybe she just needed to stool. Although having a stool reduced her girth, she still looked gray and was continuing to have more apnea and bradys. At this point, her blood gas wasn’t good so we hooked her back up to the oxygen. On the doctor’s orders, we repeated the lab work. The results confirmed that this baby had an infection, but we knew she was in trouble even before we got the lab work back.

Example 6: Flying blind

This incident occurred during a solo cross-country flight (a required part of aviation training to become a private pilot) in a Cessna 172. The pilot’s plan was for a 45-minute trip. The weather for this journey was somewhat perfect — sunny, warm, few clouds, not much haze. He had several-mile visibility, but not unlimited. He was navigating by landmarks.

The first thing he did was build a flight plan, including: heading, course, planned airspeed, planned altitude, way points in between each leg of the journey, destination (diagram of the airport), and a list of radio frequencies. His flight instructor okayed this flight plan. Then he went through his preflight routine. He got in the airplane, checked the fuel and the ignition (to make sure the engine was running properly), set the altitude (by calibrating the altimeter with the published elevation of the airport where he was located; this is pretty straightforward), and calibrated the directional gyro (DG).

He took off and turned in the direction he needed to go. During the initial several minutes of his flight, he would be flying over somewhat familiar terrain, because he had flown in this general direction several times during his training, including a dual cross-country (a cross-country flight with an instructor) to an airport in the vicinity of his intended course for that day. About a half hour into the flight, the pilot started getting the feeling that he wasn’t where he was supposed to be. Something didn’t feel right. But he couldn’t figure out where he was on the map — all the little towns looked similar.

What bothered him the most at this point was that his instruments had been telling him he was on course, so how did he get lost? He checked his DG against the compass (while flying as straight and level as he could get), and realized his DG was about 20 to 30 degrees off. That’s a very significant inaccuracy. So he stopped trusting his DG, and he had a rough estimate of how far off he was at this point. He knew he’d been going in the right general direction (south), but that he had just drifted east more than he should have.

He decided to keep flying south because he knew he would be crossing the Ohio River. This is a very obvious landmark that he could use as an anchor to discover his true position. Sure enough, the arrangement of the factories on the banks of the river was different from what he was expecting. He abandoned his expectations and tried to match the factory configuration on the river to his map. In this way, he was able to create a new hypothesis about his location.

A particular bend in the river had power plants/factories with large smokestacks. The map he had showed whether a particular vertical obstruction (like a smoke stack or radio antenna) is a single structure or multiple structures bunched together. He noted how these landmarks lined up, trying to establish a pattern to get him to the airport. He noticed a railroad crossing that was crossed by high-tension power lines. He noticed the lines first and thought, “Is this the one crossed by the railroad track that leads right into the airport?” Then he followed it straight to his destination.

In this example, we see several of the sensemaking activities. The pilot started with a good frame, in the form of a map and knowledge of how to use basic navigational equipment. Unknown to him, the equipment was malfunctioning. Nevertheless, he attempted to elaborate the frame as his journey progressed. He encountered data that made him question his frame — question his position on the map. But he explained these data away and preserved the frame. Eventually, he reached a point where the deviation was too great, and where the topology was too discrepant from his expectancies. He used some fragmentary knowledge to devise a strategy for recovering — he knew that he was heading south, and would eventually cross the Ohio River, and he prepared his maps to check his location at that time. The Ohio River was a major landmark, a dominating anchor, and he hoped he could discard all of his confused notions about location and start fresh, using the Ohio River and seeing what map features corresponded to the visual features he would spot. He also had a rough idea of how far he had drifted from his original course, so he could start his search from a likely point. He could not have successfully reoriented earlier because he simply did not have a sufficient set of useful anchors to fix his position.

Example 6 illustrates most of the sensemaking types shown in Figure 6.1. The example shows the initial data–frame match: The pilot started off with a firm belief that he knew where he was. As he proceeded, he elaborated on his frame by incorporating various landmarks. His elaboration also helped him preserve his frame, as he explained away some potential discrepancies. Eventually, he did question his understanding. He did realize that he was lost. He had no alternate frame ready as a replacement, and no easy way to construct a new frame. But he was able to devise a strategy that would let him use a few anchors (the Ohio River and the configuration of factories) to find his position on his map. He used this new frame to locate his destination airport.