Laura Militello, Robert Hutton, (Militello and Hutton 1998)

Summary

Applied cognitive task analysis

Thoughts

Notes

Abstract

Cognitive task analysis (CTA) is a set of methods for identifying cognitive skills, or mental demands, needed to perform a task proficiently. The product of the task analysis can be used to inform the design of interfaces and training systems. However, CTA is resource intensive and has previously been of limited use to design practitioners. A streamlined method of CTA, Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA), is presented in this paper. ACTA consists of three interview methods that help the practitioner to extract information about the cognitive demands and skills required for a task. ACTA also allows the practitioner to represent this information in a format that will translate more directly into applied products, such as improved training scenarios or interface recommendations. This paper will describe the three methods, an evaluation study conducted to assess the usability and usefulness of the methods, and some directions for future research for making cognitive task analysis accessible to practitioners. ACTA techniques were found to be easy to use, flexible, and to provide clear output. The information and training materials developed based on ACTA interviews were found to be accurate and important for training purposes.

Introduction

As task analytic techniques have become more sophisticated, focusing on cognitive activities as well as behaviours, they have become less accessible to practitioners. This paper introduces Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA), a set of streamlined cognitive task an alysis tools that have been developed specifically for use by professionals who have not been trained in cognitive psychology, but who do develop ap plications that can benefit from the use of cognitive task analysis.

Applied cognitive task analysis

The goal of this project was to develop and evaluate techniques that would enable instructional designers and systems designers to elicit critical cognitive elements from Subject Matter Experts (SMEs). The techniques presented here are intended to be complementary; each is designed to get at different aspects of cognitive skill.

- The first technique, the task diagram interview, provides the interviewer with a broad overview of the task and highlights the difficult cognitive portions of the task to be probed further with in-depth interviews.

- The second technique, the knowledge audit, surveys the aspects of expertise required for a specific task or subtask. As each aspect of expertise is uncovered, it is probed for concrete examples in the context of the job, cues and strategies used, and why it presents a challenge to inexperienced people.

- The third technique, the simulation interview, allows the interviewer to probe the cognitive processes of the SMEs within the context of a specific scenario. The use of a simulation or scenario provides job context that is difficult to obtain via the other interview techniques, and therefore allows additional probing around issues such as situation assessment, how situation assessment impacts a course of action, and potential errors that a novice would be likely to make given the same situation.

- Finally, a cognitive demands table is offered as a means to consolidate and synthesize the data, so that it can be directly applied to a specific project.

[formatting mine]

Task diagram

The task diagram elicits a broad overview of the task and identifies the difficult cognitive elements. Although this preliminary interview offers only a surface-level view of the cognitive elements of the task, it enables the interviewer to focus the more in-depth interviews (i.e. the knowledge audit and simulation interviews) so that time and resources can be spent unpacking the most difficult and relevant of those cognitive elements.

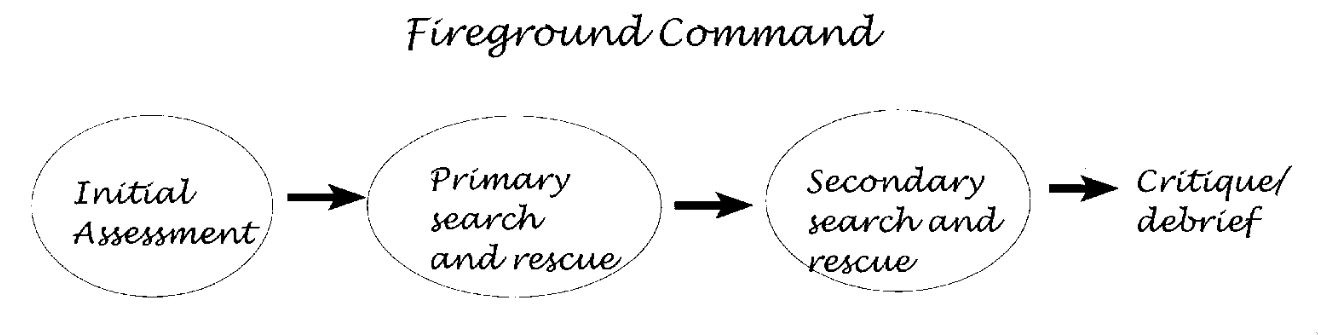

The subject matter expert is asked to decompose the task into steps or subtasks with a question such as, `Think about what you do when you (task of interest). Can you break this task down into less than six, but more than three steps?’ The goal is to get the expert to walk through the task in his / her mind, verbalizing major steps. The interviewer limits the SME to between three and six steps, to ensure that time is not wasted delving into minute detail during the surface-level interview. After the steps of the task have been articulated, the SME is asked to identify which of the steps require cognitive skill, with a question such as, `Of the steps you have just identified which require difficult cognitive skills? By cognitive skills I mean judgements, assessments, problem solving ± thinking skills’. The resulting diagram (figure 1) serves as a road map for future interviews, providing an overview of the major steps involved in the task and the sequence in which the steps are carried out, as well as which of the steps require the most cognitive skill.

The task diagram interview is intended to provide a surface-level look at the task, and does not attempt to unpack the mental model of each SME. The goal is to elicit a very broad overview of the task.

Knowledge audit

The knowledge audit identifies ways in which expertise is used in a domain and provides examples based on actual experience. […]

The knowledge audit employs a set of probes designed to describe types of domain knowledge or skill and elicit appropriate examples (figure 2). The goal is not simply to find out whether each component is present in the task, but to find out the nature of these skills, specific events where they were required, strategies that have been used, and so forth. The list of probes is the starting point for conducting this interview. Then, the interviewer asks for specifics about the example in terms of critical cues and strategies of decision making. This is followed by a discussion of potential errors that a novice, less-experienced person might have made in this situation.

[…]

Basic probes:

Past & Future

Experts can figure out how a situation developed, and they can think into the future to see where the situation is going. Amongst other things, this can allow experts to head off problems before they develop.

Is there a time when you walked into the middle of a situation and knew exactly how things got there and where they were headed?

Big Picture

Novices may only see bits and pieces. Experts are able to quickly build an understanding of the whole situation — the Big Picture view. This allows the expert to think about how different elements fit together and affect each other.

Can you give me an example of what is important about the Big Picture for this task? What are the major elements you have to know and keep track of?

Noticing

Experts are able to detect cues and see meaningful patterns that less-experienced personnel may miss altogether.

Have you had experiences where part of a situation just ‘popped’ out at you; where you noticed things going on that others didn’t catch? What is an example?

Job Smarts

Experts learn how to combine procedures and work the task in the most efficient way possible. They don’t cut corners, but they don’t waste time and resources either.

When you do this task, are there ways of working smart or accomplishing more with less — that you have found especially useful?

Opportunities/Improvising

Experts are comfortable improvising — seeing what will work in this particular situation; they are able to shift directions to take advantage of opportunities.

Can you think of an example when you have improvised in this task or noticed an opportunity to do something better?

Self-Monitoring

Experts are aware of their performance; they check how they are doing and make adjustments. Experts notice when their performance is not what it should be (this could be due to stress, fatigue, high workload, etc) and are able to adjust so that the job gets done.

Can you think of a time when you realised that you would need to change the way you were performing in order to get the job done?

Optional Probes:

Anomalies

Novices don’t know what is typical, so they have a hard time identifying what is atypical. Experts can quickly spot unusual events and detect deviations. And, they are able to notice when something that ought to happen, doesn’t.

Can you describe an instance when you spotted a deviation from the norm, or knew something was amiss?

Equipment Difficulties

Equipment can sometimes mislead. Novices usually believe whatever the equipment tells them; they don’t know when to be skeptical.

Have there been times when the equipment pointed in one direction, but your own judgment told you to do something else? Or when you had to rely on experience to avoid being led astray by the equipment?

Table 1. Example of a knowledge audit table.

Aspects of expertise Cues and strategies Why difficult? Past and future; e.g. Explosions in office strip — search the office areas rather than source of explosion Material safety data sheets (MSDS) tells you that explosion in area of dangerous chemicals and information about chemicals. Start where most likely to find victims and own safety considerations Novice would be trained to start at source and work out. May not look at MSDS, to find potential source of explosion, and account for where people are most likely to be. Big picture; includes source of hazard, potential location of victims, ingress/egress routes, other hazards Senses, communication with others, building owners, MSDS, building pre-plans Novice get tunnel vision, focuses on one thing e.g . victims Noticing; breathing sounds of victims Both you and your partner stop, hold your breath, and listen. Listen for crying, talking to themselves, victims knocking things over. Noise from own breathing in apparatus, fire noises. Don’t know what kinds of sounds to listen for. [formatting mine]

Simulation interview

The simulation interview allows the interviewer to better understand the SME’s cognitive processes within the context of an incident. […]

The simulation interview is based on presentation of a challenging scenario to the SME. The authors recommend that the interviewer retrieves a scenario that already exists for use in this interview. Often, simulations and scenarios exist for training purposes. It may be necessary to adapt or modify the scenario to conform to practical constraints such as time limitations. Developing a new simulation specifically for use in the interview is not a trivial task and is likely to require an upfront CTA in order to gather the foundational information needed to present a challenging situation. The simulation can be in the form of a paper-and-pencil exercise, perhaps using maps or other diagrams. In some settings it may be possible to use video or computer-supported simulations. Surprisingly, in the authors’ experience, the fidelity of the simulation is not an important issue. The key is that the simulation presents a challenging scenario.

After exposure to the simulation, the SME is asked to identify major events, including judgements and decisions, with a question such as, `As you experience this simulation, imagine you are the (job you are investigating) in the incident. Afterwards, I am going to ask you a series of questions about how you would think and act in this situation’. Each event is probed for situation assessment, actions, critical cues, and potential errors surrounding that event (figure 3).

Information elicited is recorded in the simulation interview table (table 2). Using the same simulation for interviews with multiple SMEs can provide insight into situations in which more than one action would be acceptable, and alternative assessments of the same situation are plausible. This technique can be used to highlight differing SME perspectives, which is important information for developing training and system design recommendations. The technique can also be used to contrast expert and novice perspectives by conducting interviews with people of differing levels of expertise using the same simulation.

Figure 3. Simulation interview probes

For each major event, elicit the following information

- As the (job you are investigating) in this scenario, what actions, if any, would you take at this point in time?

- What do you think is going on here? What is your assessment at this point in time?

- What pieces of information led you to this situation assessment and these actions?

- What errors would an inexperienced person be likely to make in this situation?

Table 2. Example of a simulation interview table.

Events Actions Assessment Critical cues Potential errors On-scene arrival (1) Account for people (names), (2) Ask neighbors (but don’t take their word for it, check it out yourself), (3) must knock on or knock down to make sure people aren’t there It’s a cold night, need to find place for people who have been evacuated (1) Night time, (2) cold -> 15°, (3) Dead space, (4) Add on floor, (5), Poor materials wood (punk board), metal girders (buckle and break under fire), (6) common attack in whole building Not keeping track of people (could be looking for people who are not there) Initial attack (1) Watch for signs of building collapse, (2) if signs of building collapse, evacuate and throw water on it from outside Faulty construction, building may collapse (1) Signs of building collapse include: What walls are doing: cracking; What floors are doing: groaning; What metal girders are doing: clicking, popping, (2) cable in old buildings hold walls together Ventilating the attack, this draws the fire up and spreads it through the pipes and electrical system [formatting mine]

Cognitive demands table

After conducting ACTA interviews with multiple SMEs, the authors recommend the use of a cognitive demands table (table 3) to sort through and analyse the data. Clearly, not every bit of information discussed in an interview will be relevant for the goals of a specific project. The cognitive demands table is intended to provide a format for the practitioner to use in focusing the analysis on project goals. The authors offer sample headings for the table based on analyses that they have conducted in the past (difficult cognitive element, why difficult, comm on errors, and cues and strategies used), but recommend that practitioners focus on the types of information that they will need to develop a new course or design a new system. The table also helps the practitioner see common themes in the data, as well as conflicting information given by multiple SMEs.

Table 3. Example of a cognitive demands table

Difficult cognitive element Why difficult? Common errors Cues and strategies used Knowing where to search after an explosion (1) Novices may not be trained in dealing with explosions. Other training suggests you should start at the source and work outward; (2) Not everyone knows about the Material Safety Data Sheets. These contain critical information Novice would be likely to start at the source of the explosion. Starting at the source is a rule of thumb for most other kinds of incidents (1) Start where you are most likely to find victims, keeping in mind safety considerations; (2) Refer to Material Safety Data Sheets to determine where dangerous chemicals are likely to be; (3) Consider the type of structure and where victims are likely to be; (4) Consider the likelihood of further explosions. Keep in mind the safety of your crew Finding victims in a burning building There are lots of distracting noises. If you are nervous or tired, your own breathing makes it hard to hear anything else Novices sometimes don’t recognize recognize their own breathing sounds; they mistakenly think they hear a victim breathing (1) Both you and your partner stop, hold your breath, and listen; (2) Listen for crying, victims talking to themselves, victims knocking things over, etc [formatting mine]